Two notable humans reached a century of existence this year, only to then depart from this crazy world. But, despite this tenuous link of both living to 100 years of age, I would however posit that Mike Grgich left a far more pleasing legacy than Henry Kissinger.

While the great, Sequoia sempervirens likely scoffs at us from the vantage of its 2,000 year lifespan, even “just” a century is an exceedingly long time to be around. This is shown in the fact that it was only in the second half of his life that Grgich founded his winery, Grgich-Hills which what established his legacy in the wine world, now producing nearly a million bottles a year and controlling 140ha of vineyards in Napa. At a touch less than half a century in age myself, I look at someone like Grgich and see that sometimes it is your second act that proves the memorable one.

Grgich died on 13 December and I won’t get into the family history as it’s been well covered. What’s worth adding is that he was part of an age in Napa Valley where to make wine, one needed to be 50% winemaker and 50% showman. His former boss, Robert Mondavi, definitely tilted heavier on the latter and today, it’s more like 5% winemaker and 95% huge money if one is even still able to start something in Napa from the ground up.

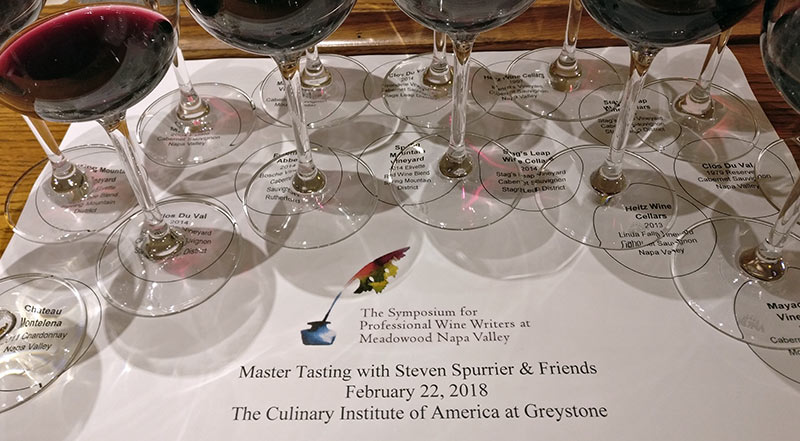

Grgich found his way into various narratives of wine history, often by patiently nudging his way into them. The irony of this is that he was then completely excised as a character from the rather awful film, Bottle Shock, despite being truly key to the history of Château Montelena given that he was a winemaker of the award-winning Chardonnay presented at the Judgment of Paris.

It was however another part of his life story that intrigued me about Grgich which was his interest in trying to find the origin of Zinfandel. Grgich had always claimed that he “noted similarities” between Zinfandel and Plavac Mali, the main red grape variety of his native lands in Dalmatia. He told me in an interview in October of 2008, “When I saw the Zinfandel coming in at [Château] Souverain, it looked like Plavac Mali. Same leaves. Same mix of ripe and underripe berries.”

As an aside, I would like to mention that it seems Zinfandel seems to speak to many an immigrant Croatian as my great-grandfather, while being from the interior, Plešivica region of Croatia, only drank Zinfandel until the end of his days, living in San Francisco, never aware of it actually being the taste of an ancestral home he never returned to.

The work that would eventually show the variety connections in 2000 was ultimately performed by Dr. Carole Meredith via DNA research and a bit of luck from some old vines in Croatia. In addition to finding that Zinfandel indeed came from Croatia, she and her team also found that it is one parent of Plavac Mali.

Despite not being part of the scientific research other than stating a hunch that “no one listened to at the time because it was the immigrant saying it”, I still wanted to talk to Grgich about the wines of Dalmatia as he’d opened one of the first, modern wineries there after the fall of Yugoslavia. And well, he’s also quite a character.

This is why I interviewed him all those years ago. I went up to Grgich-Hills one day to have a chat which I’m reprinting here, edited for length as only portions of it were used in my little Dalmatia book I published 15 years ago.

Tell me a bit about your origins in Croatia.

We were from Desne [just to the east of Ploče in Southern Dalmatia], in the Neretva Delta and were a people who made our living from farming and fishing, but winemaking had been with us for generations.

During the Communism period, they planted more grapes in the delta, but it was a terrible region for vine growing as it would flood and put down lots of nutrients. Nowadays it’s just for growing Mandarins.

What was winemaking based upon in the region in terms of varieties?

There was Plavac Mali, but it was really mixed in terms of plantings. Plavka was another variety but there were so many of them I can’t even remember all the names now as most of them don’t really exist today as communism changed everything.

Tell me a bit more about the Communist period of Yugoslavia. Did that affect your approach to winemaking?

Well, I did my studies in Zagreb and then basically left, but it was a period that changed things a great deal as before Communism we were 80% farmers. Imagine that as in America it’s now 5-6%, but once Communism was over, it had dropped to about 40%. Everyone got chased to the factories and government jobs.

But if Communism did one thing for Croatia, it’s that it educated everyone which has helped all aspects of life, especially the winemaking.

What happened once Communism fell?

It allowed me to challenge my countrymen.

Communism was elected out of office in April of 1990. I was over there in May, seeing what I could do to improve the country.

I talked to President Tuđman who asked me, “What you are doing in America?” I said, “Making wine.” “Why don’t you make one here?” And so I started to, but it took me a long time to get permits to open a winery because it was still communism despite it officially being over. There were the same people in government and a great deal of resistance and inefficiency.

It took my three years to finally get going and only after getting a personal intervention by the president via the courts. I had to ship in all the equipment from outside as I wanted to create a world-class winery.

So you managed to finally get started in…?

In 1996 I managed to make my first vintage there. The 1997 vintage was chosen to represent Croatia at the United Nations.

For the first vintages I was going over every year to select the grapes but in the last few years my nephew, Ivo Jeremaz, who is the winemaker here at Grgich-Hills has been going.

What’s interesting is that your grapes for the wines come from the Dingač region, but you just call it ‘Plavac Mali’? Why don’t you take advantage of this well-known region’s name?

Yes, I did that on purpose as I didn’t want to compete with the Dingač producers.

Dingač vs. Grgić wouldn’t have been good for anyone. It’s already been a problem with the Pošip grapes because once I came everyone on Korčula wanted to sell to me instead of just to the main co-op.

Why did you open in Pelješac and not in Neretva, your homeland?

I was looking to open in the highest quality region and this is where it is and I was also able to find an old military building in Trstenik to make use of.

I didn’t open the winery for business, but to be a modern winery and to make quality wines. Nobody opens a winery with just 3,000 cases [36,000 bottles] as it’s too small. It does pay its bills however.

Before establishing the winery, something like 50% of Croatian wine in the region was made with sugar and water with a bit of pomace [piquette] and I was simply embarrassed at what was being produced in my country.

I don’t take credit for the modernization in Croatia, but there was a clear need for setting up a world-class, and state-of-the-art cellar to make a higher quality of wine than had existed.

Do you have any of your own vines?

My family lost all its vineyards at the time due to communism but I now own 2ha of my own. I wanted to buy more, but some Americans started moving in and paying 10 times more than what I paid! It just wasn’t economically feasible to buy more and honestly, people don’t really want to sell as they have vines that have been in their families for generations.

What do you think of the new generation taking over from their parents in the country?

They’re not stuck in anything and they have more open minds and can try things.

Luckily for them, they can get beyond the traditional winemaking which is how I’ve always made wine and this is really going to benefit them. When I was growing up, we suffered for opportunity and so we were stuck following tradition. The newer generations have a great future in front of them.