The research papers for Master of Wine candidates don’t often receive a lot of attention once released for public consumption as they’re quite focused and specialized, sometimes to a fault. It would however seem that New Zealand winemaker Sophie Parker-Thomson’s paper is the exception and for good reason. It’s one of the first thorough research projects that collates various studies while conducting a massive one of her own to put forth the proposal that headaches in wines have little to do with sulfur dioxide (aka sulfites) and more to do with a complex set of what are called “amines”.

Her paper is long, detailed, and full of things I had to look up on Wikipedia as I’m not a professional winemaker like she is but it’s very much worth the read, all 117 pages of it. There are a lot of science-y bits throughout and you’ll need to take time to get through it and fully digest it, but it’s a welcome text on this needlessly polemic subject.

It is worth mentioning that discussions about biogenic amines have been around for many years. Sophie in fact states this in the opening line of her abstract, “Vast research exists on biogenic amines (BAs) in food and beverages due to the toxicological impacts they have on health in addition to their negative quality implications.”

If you want a nutshell explanation of this complex topic, I’m very happy to post this excerpt from my Georgian wine book. It’s from an interview with the very knowledgeable Catalan wine scientist (enologist doesn’t give him enough due), Raül Bobet who owns the wineries Ferrer-Bobet in Priorat as well as Castell d’Encús in the pre-Pyrénées.

Back in 2017 I asked him about this subject as I wanted to include it in the Georgia book due to the tendency of those working via kvevri to eschew the use of sulfites and here’s what he said:

“SO2 (sulphur dioxide) is a very reactive molecule that binds with different types of wine compounds (aldehydes, phenols, etc.) that play a role in forming a wine’s aroma. In that sense minimizing the usage of sulfites is a reasonable practice in winemaking. The efficiency of it however, depends very much on the wine’s pH due to the higher activity of the molecular form of sulfites. From the sensorial point of view, sulfites mask some of the effects of the oxidation because of how they bind quickly with aldehydes, as well as partially preventing oxidation because their redox potential. Another quite important aspect is related to the prevention of bacterial growth and yeast development.

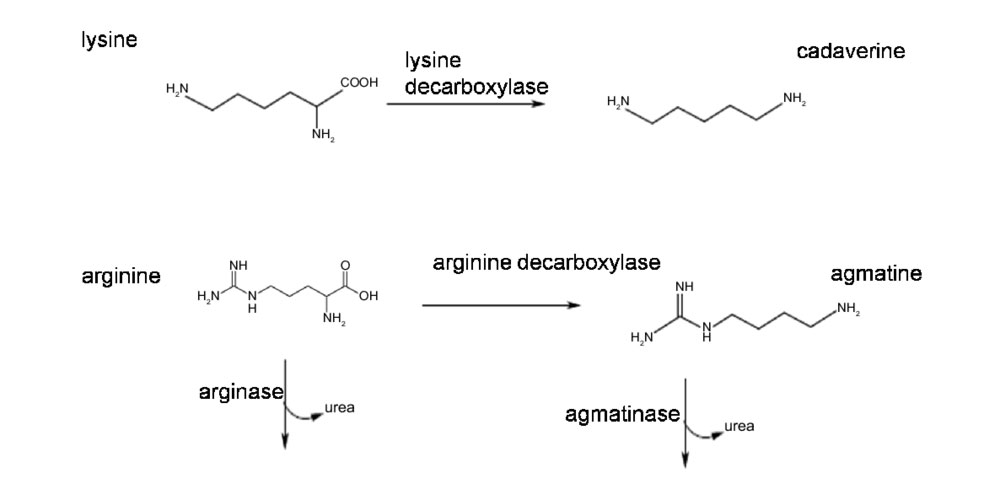

When a wine has no sulfites added and passes through malolactic conversion, byproducts can occur after the transformation of all the malic acid as a consequence of existing residual bacteria. The result is considerable amounts of biogenic amines (histamine, cadaverine, putrescine, etc.) There are some people that are quite allergic to histamines for example which can result in adverse health effects.

What this means is that besides the known disadvantages of too much SO2 in wine, it’s also the case that with no sulfites at all, similar health problems may occur to those susceptible in addition to potential spoilage of the wine, especially in high pH wines.

For me, this was one of the more interesting parts in my book and reinforced that the full exclusion of SO2 from winemaking is simply madness. People have become convinced that SO2 is something evil and don’t really seem to want to hear otherwise. The above excerpt (as well as my taking a critical look at what kvevri wine production can and can’t do, or the contradiction between making “natural” wine with non-organically-grown grapes) was met with considerable backlash from certain Georgian producers who have built up their international reputation on the “blind natural” approach to winemaking. Ironically, despite this public front, they do add SO2 at bottling but refuse to talk about it.

This topic of the biogenic amines should have been widely addressed long ago as it’s not just Georgia where this has become problematic. One example is the quite horrid physical reactions I’ve had to some of the well-known wines from Foradori in Italy as well as others from around Spain where I live.

It’s to the point where I refuse to drink anything made in this fashion anymore given that there is a high probability of toxic elements developing which may or may not affect me in a detrimental way. I’ve never had such issues in wines with SO2 added given that its quantities are regulated. And again, there is a potential issue with SO2 which can affect “3–10% of the acute asthmatic population” but in those cases, it’s not a headache reaction, but more of a respiratory reaction.

Undoubtedly there will be those who ignore Sophie’s work given that it’s from the “establishment” and the avoidance of using SO2 in winemaking is a cornerstone to “natural” wine.

But if studies like Sophie’s excellent paper can reach a wider wine drinking public and get them to realize that it’s not the sulfites giving them a headache but perhaps something else such as these biogenic amines, then we can get beyond the current no SO2 silliness. She says: “Most wine intolerance complaints, including from asthmatics, arise after the consumption of red wine, which is contrary to the reality of relative SO2 levels: white wines and sparkling wines typically contain more than red.”

SO2 is a preventative additive and the sooner the greater wine drinking public can realize this, the sooner we can hopefully get behind approaching the real issues as to why one gets a headache from certain wines.

You’re reading a free article on Hudin.com.

Please consider subscribing to support independent journalism and get access to regional wine reports as well as insider information on the wine world.

Excellent article, Miquel, it makes perfect sense to me. Not because I fully understand from an oenological point of view, but it confirms my personal experience of suffering from headaches especially with red wine from warm areas (and high pH soils). I’ve always linked it to the higher alcohol level, but it doesn’t happen with the whites. So I find this information really interesting, because it adds other possibilities. I’ll try to read more about this. Thanks

It has less to do with the soil and more to do with an absence of SO2, ie “natural” wine, so if drinking those makes you feel off, that’s definitely a probable cause.