“Influencer” is a word many of us will have heard of at this point even if not in marketing circles where it’s the current brass ring in terms of social media advertising campaigns. In brief, the influencer is someone on social media (usually Instagram these days) whose mere mention of a specific body cream, vitamin supplement, or possibly even laxative can make sales soar. Likewise, their denouncing a product can theoretically tank it, thus why they’ve been deemed, “influencers”.

In its most blatant form, the influencer will simply pose with the product and say something positively banal about it. In the more insidious form, the product is incorporated into a photo (or perhaps a tweet) and is more akin to the older practice of product placement that’s been with us for decades in film and television.

The principle is based upon the fact that product ads don’t really work anymore and this “genuine authority” offhandedly mentioning your product will lead to their followers putting faith in the product. To a large extent, this has been effective both for product promotion as well as “influencers”. People like the Kardashians, in addition to stealing the souls of orphaned children at night in order to replenish their alien life force, use these paid “influencings” to fund their otherwise vapid lives.

This has not gone unnoticed and so many would-be influencers have sprouted up in recent times to offer their placing of whatever you like in their photos to feed their “thousands of engaged followers”. It’s slowly slipped into the wine world as an “authentic voice” in wine is someone who can move bottles and someone marketers are more than a little hungry for. Wine advertising is probably one of the most difficult sectors there are given perceptions of wine being elitist and snobby. Thus influencers are seen as a way to break out of this as pushing a wine brand outside these circles because otherwise, it’s like trying to put your cat on a diet. Thus, finding that rare soul who can “cut through the crap” is highly desirable.

Beyond the legal issues of wine being an alcohol, there are also regulations in terms of influencers promoting a product as this constitutes a paid sponsorship and entities such as the Federal Trade Commission in the United States require that it be plainly stated that an ad is an ad. Just how this should be done has yet to be figured out perfectly, although adding #ad seems to be the most reasonable approach.

There are however few who want to do this, especially in wine as #ad suddenly breaks the suspension of authenticity. Is the influencer posting a wine for their followers because they believe it in or simply because they were paid to say that they do? And thus, the promotion will readily fail as authenticity (much like egos) in wine is an extremely fragile construct. But this issue of being paid to promote a wine or not pales in how easy it is to actually fake being an influencer.

Influence bought and followed

The old way people would fake their supposed influence would be to buy followers. This was and I assume, still is extremely easy to do on Twitter. Despite Twitter having cracked down on fake bot accounts, it’s still very easy to pump up fake followers but then you’ll see that tweets and more importantly clicking through on links in tweets does not add up to the followers claimed. This is where Instagram has become a vastly different beast.

In case you’ve not heard of “Instagram pods”, have a read as due to it being somewhat harder to buy fake followers on Instagram (although still possible) and Instagram’s algorithm making it harder to fake likes, the “pods” have sprouted up like mushrooms recently because influencer product placement rates have skyrocketed.

Basically, how it works is that they game the Instagram algorithm. A member of a pod (an informal group that communicates via a third medium such as Telegram) will announce to everyone that they’ve posted a new photo. Everyone in the pod already follows each other and they’ll then go in and like it quickly, boosting its perceived interest on the platform and thus making it more visible for others, potentially having it “go viral”.

This is all down to using Instagram’s algorithm (which I passionately hate as it destroyed what was a fun medium) against itself in order to boost people to influencer status. “What’s the harm in this?” you may ask as it’s similar to how movie producers shuck around a project to generate interest or how politicians make themselves known. If you will, the Trump rallies were essentially “pods” (or more accurately “bots”) that worked to boost his profile in a field of Republican candidates in 2016.

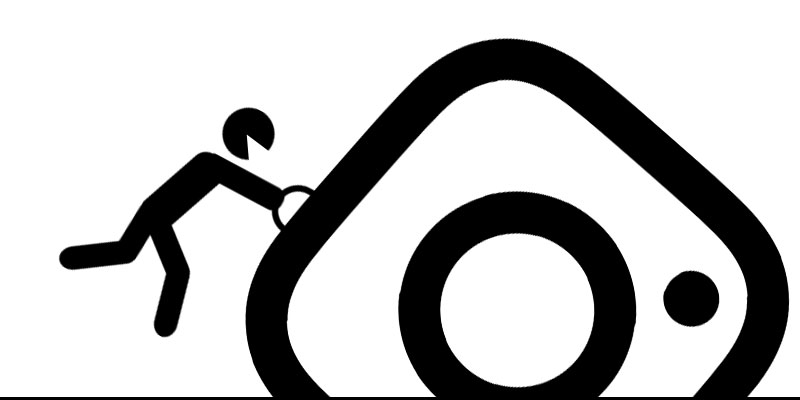

The issue is that these people aren’t actually influencing anything. They are simply getting likes from a group of people not interested in their photos but boosting their own profiles and no one benefits from this. If someone then pays them to promote a product, this constitutes fraud as it’s entering into an agreement (paid promotion of a product) based upon what are perceived to be factual and contractual items (perceived influencer has X number of followers who view product and potentially buy it) when the second part of that isn’t true at all. It would be akin to agreeing to surgery because the doctor claims to have graduated from Harvard when in fact, he has no medical license at all.

The influencers in wine are pretty small operations at this point but they keep growing and increasing as marketers keep turning to them more and they keep sucking up more of the already slim budgets wineries have for promotion. While this article is in Spanish the key takeaways from it are that one in every four influencers is fraudulent and one in every five likes they have is one they paid for. I don’t think this even takes into account this issue of pods which, while clever, has made a difficult situation even harder as it’s estimated to be somewhere north of $1bn spent annually on “influencer campaigns” although few want to talk about it for all the aforementioned perception issues.

Know how to spot your Fake Influencer (#flafencer?)

But if the manner in which these people work is so obfuscated by pods and whatever else, how do you find them out?

There are several tells, the first being the engagement rate vs follower count and anything over 10-12% should immediately be suspect. Instagram’s algorithm will keep most any photo at around 4-5% of likes of the total followers. Have 1,000 followers? Most of your photos will get around 50 likes. Don’t ask me why it’s like this, but I’ve seen it time and again and it appears that the more followers one has, the more it drifts to 4% instead of 5%.

People who I would bet a great deal of money as to not be buying followers nor using pods would be @jancisrobinson, @timatkinmw, and @drjamiegoode to name a few. Jancis and Tim are Masters of Wine with a great deal of respect and history of writing about wine. Jamie, while not an MW has gained a great deal of following, written several books, and he does a very good job of engaging people in social media.

All of these accounts usually follow the 4% engagement rule with the occasional photo rising above that rarely and almost never exceedingly 10%. Another great example is my co-author on the Georgia book, @darikomogzauri. She’s extremely engaged in Instagram and is generally seeing about 4-5% of her total follower count in terms of likes with the very infrequent peak to 7%

For a fake wine influencer, you’ll see much higher totals, sometimes peaking at 20% which is not just abnormal for Instagram, it’s nearly impossible these days. I say this because wine is inherently not exciting to look at, only to drink. Wine will never be the latest shoe from Nike, nor SpaceX landing two booster rockets side by side, which, sorry, I still find fucking awesome.

Then there’s the photo history of potential fake influencer accounts. You’ll see that if you scroll back on anyone legitimate in wine, there is slow growth. You can scroll back on my meager account @mhudin and see that like and follower growth were very slow and gradual, same goes for @vinologue which is actually a testament to how the algorithm really choked off heavy engagement as it grew steadily and then dropped once the algorithm gnashed its teeth.

In case you want more tells of fake influencers, look at the comments. People deep into wine are pretty geeky and so if they comment, it’s pretty specific. Post a photo of a Burgundy Chardonnay from 2005 and someone will probably quip back, “How’s the Premox?” If you don’t know what that means, you probably don’t follow a lot of wine people.

If however, someone is engaging in pod tactics, the comments are a great deal dumber. “Nice shot!” “Hey cool!” “Great!” and the such rule the day. More important is that you go and click on the profile of the commenter and you’ll more often than not find someone with (surprise, surprise) a very similar number of followers, a very similar number of likes, and a very similar follower/like ratio that exceeds what is typical. Why? Because they’re all part of the same pod, building each other up. It may not always be symmetric but it certainly won’t look organic.

But all of this isn’t written in stone and things could change with pods being replaced by, I don’t know, “tubes” or something and the methodology being employed to counter some new change to the Instagram algorithm or even some other social media that comes along. The key is to always question it as it’s an industry of promotion that has built itself upon its own fame. Let’s not forget that Kim Kardashian got famous for having a “celebrity” sex tape… before she was a celebrity but that sex tape then made her a celebrity and… it just hurts my head to understand this any further.

The moral of the story is the extremely old adage that “if it seems to be too good to be true, it probably is”. If someone is claiming to be an influencer in wine, but you’ve never heard of them and they’ve popped out of nowhere, chances are, they’re probably not and are just part of the nameless hordes trying to take shortcuts to get freebies (wine, books, etc.), free trips, or possibly some degree of suposed “fame”, instead of putting in the painful hours it takes to get there.

You’re reading a free article on Hudin.com.

Please consider subscribing to support independent journalism and get access to regional wine reports as well as insider information on the wine world.